Bags of rocks at the LME warehouses

A while ago there was a series of large breakdowns in the Nickle market as traded at the London Metal Exchange. Put simply there wasn't enough of the real metal to back the trades being made on the market. Put really simply there isn't enough quality collateral to back the volume of derivatives trading we are seeing. With the markets contracting this will start to cause a lot of problems.

We see this in a number of commodities markets today, there's a large amount of trade volume that can exist without there being enough actual commodities to back it all up if everyone were to want to have the collateral returned to them. Markets can actually operate like this for a long time, perhaps punctuated with large crises from time to time. The average person really seems to not understand that things are structured this way, probably because while times are good you don't need to know the plumbing of the markets. The reason these markets can continue to function is that if there's enough that at any given time only some percentage of the traders want to actually get delivery of the underlying commodity that the contracts are trading on top of.

Having a fractional reserve system for commodities creates a number of game theoretic pressures over the long term, and ones that are eventually destabilizing. One such pressure is that if traders don't actually want to get delivery of the underlying commodities all that often it ends up being much cheaper to run a market that can't deliver all of those commodities. For starters you can save a lot of warehousing expenses if you don't have to warehouse as much of the underlying commodities, the extreme case is not warehousing anything but confidence can collapse very fast in such a case. While a fractional reserve system is good for some parties it tends to reduce the resilience of the markets themselves to various shocks. It also creates enormous incentives to cheat about how much real collateral is backing each derivative contract. The act of rehypothecation is common, this is a situation where each unit of the underlying commodity is pledged more than once to support derivative contracts. A fractional system pretty much directly implies the existence of rehypothecation. The issue with rehypothecation is that once it starts its hard to stop, where's the line in the sand where you can say there is too much? When times are "good" this scheme doesn't run into problems, but when events happen that make collateral more scarce you end up with a volatile situation where confidence in deliveries from a market can crater quickly. This matters because the commodities markets distinguish themselves from mere casinos because of the underlying connection they are supposed to have to the actual commodities that they are trading. This is a core component of what gives these market participants confidence and what gives the markets themselves legitimacy. Some of the customers that require the delivery of the materials, for example industrial demand, are a crucial aspect of what underpins the value of commodities on the broader market. Those industrial users simply can't use paper contracts to run their businesses, they need to get the actual commodities delivered to them.

We saw one such shock last year in the Nickle market as traded on the London Metals Exchange. There wasn't enough real Nickle metals available to support the volume of trade on the market, and the market failed. There were a number of large implication for this market failure. Perhaps the most publicly obvious sign of this was that the price of Nickle jumped enormously in the space of a week in a very discontinuous manner.

A larger event however was that the LME took the unprecedented step of retroactively cancelling a large number of trades. This should really have shaken any rational traders confidence in the LME as a market, knowing that the market could just cancel your winning trades after the fact makes such a market far less desirable to trade on1.

The most recent scandal is almost comical, though likely comes as no surprise in a system that has such uncontrolled rehypothecation. LME Nickle inventories are once again called into question because some of the warehoused goods turned out to actually be bags of rocks. It sounds absurd but I'm not making this up, bags of rocks were found in a Rotterdam warehouse. Supposedly this was only 0.14% of Nickle inventories, but the point is again about confidence, if bags of rocks have been counted in the inventory numbers since at least 2022 the natural question you should be asking, is how accurate are the real numbers and who's doing the auditing? The legacy media is downplaying it, in the linked article the Bloomberg authors say "The amount of metal represents just 0.14% of live nickel inventories on the LME, worth about $1.3 million at current prices, so the immediate impact on metals markets is limited.". But I really am not so sure, in determining trustworthyness it's not the percentages that matter here but the transgressiveness of behavior that's been displayed. If I was an industrial supplier or consumer I'd start to be asking if this was an exchange I'd be willing to deal with at all. Trust isn't measured in tenths of percentage points.

The original nickle market breakdown had far more implications than just nickle and I think is part of a much longer term crisis that has been developing. This crisis is a widespread counterparty risk bubble, and defaults due to counterparties are just a symptom and these issues are coming up in many places. What has enabled this crisis is a proliferation of financial contracts and derivatives that have become increasingly detached from concrete economic outputs in the real economy. There's a very real breakdown in trust that people are seeing. As a direct result people are increasingly wanting to have better collateral or collateral with fewer counterparties in the chain. Some people are consciously aware of this shift but many are not yet at this stage of awareness, some are ignorant that they even mock people who are ahead of the curve. The general economy is doing way worse and as a result money is now starting to move downwards on Exeter's pyramid:

What Exeter's pyramid is getting at is partially economics but partially a result of psychology. When there's increased risk from your counterparties you'll naturally want safer collateral to feel better about your positions. Some markets have started to see a scramble for good collateral. In the case of commodities this means that people who need the commodities for industrial uses have been less willing to engage in derivative contracts and are instead getting increasingly creating other contracts to ensure delivery. These companies are showing with their actions that they are willing to pay more than the futures price in order to get the commodities they need without the risk of the futures market not delivering. Its very telling that the spot price is artificially low given the rise of off-exchange trades that are happening at premium above spot price and futures front month contract prices.

We are now seeing a scramble for collateral in the treasuries market developing as well. This, much like the events around the LME Nickle scandals, is a flight to safer collateral. Again we see an example of money moving down Exeter's pyramid. When people are faced with an acute shortage of collateral they will start to make decisions that seem to be irrational in times of easier collateral.

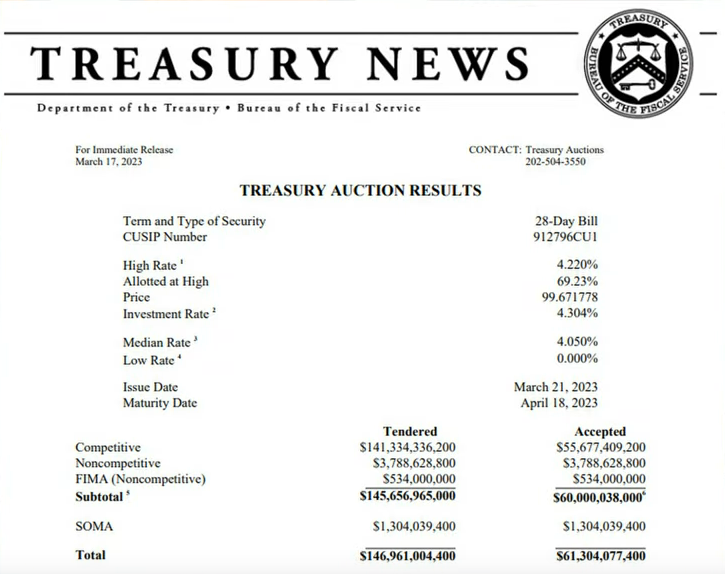

For example at the moment there are people purchasing 4 week USA Treasury Bills at 0% interest. Here's the auction results:

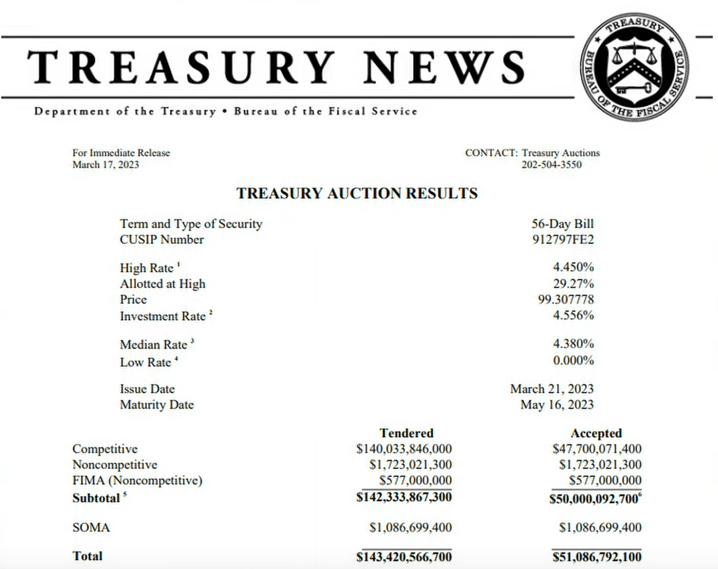

Even more crazy is the 8 week Treasury Bills seeing bids for 0%!

What the "low rate" here means is that there's people who are willing to purchase a treasury bill paying 0% interest where in 4 or 8 weeks time they are getting a promise to be paid back the exact same amount. Without considering the context it seems crazy to take on such a deal, and many people who neglect to think about the context are left assuming that these people are just stupid, when really there's more to this situation than the casual observer understands. As the saying goes "One mans junk is another mans treasury". Whenever you see these sorts of trades you should always be asking what the alternatives are. Always be asking "compared to what?" when considering the quality of collateral. In many cases you might be seeing people take the least bad option, which psychologically isn't obvious because people get so hung up on the idea that a "bad" option is being taken.

These purchases are being made by a number of large organizations, and while it might seem nonsensical to an outside observer there's a number of reasons why this is happening. Many large organizations make use of repurchase agreements via the repurchase agreement market, often referred to as the Repo Market. These deals end up being a large factor in how companies fund their short term operations.

For the most part large companies don't like to leave large amounts of cash in a bank. The recent collapse of Silicon Valley Bank should show you exactly why, the risk of having a large amount of uninsured deposits in any single bank is just too high. Bank accounts are NOT bailments, meaning you do not own the money in your bank account, and every worthwhile professional risk manager knows this fact. Even in a sick economy like we have today where many people have come to expect bailouts (meaning the taxpayer is assumed to pay for other people's mistakes) the risk of leaving a large deposit in a bank account is something that any sensible risk manager will attempt to mitigate for reasons of pure expediency. Even if there is a bailout coming it could be a while before a company had access to this money, and in that time a company could face very severe operational consequences like not being able to make payroll or not be able to pay their suppliers.

The difference between T-Bills and commodities is that T-Bills can be created out of thin air in an auction. The same can't be said about the commodities, if there's not enough commodities to back the trade made on top of them then there's not enough, industrial users just simply won't get what they need. And delivering bags of rocks might not suffice. Getting 0% on a treasury doesn't sound so bad if the alternative is bags of rocks in a warehouse.

-

This of course is assuming that there is no fraud going on, there's a lot of situations where a rational actor might make trades that look crazy if there's some form of fraud that is enriching them in the process. We see an example of this with the bailouts, making trades with a higher standard deviation of outcomes makes sense if you can force someone else to pay for your losses when you encounter losses. This is of course completely contrary to the portfolio management strategies that you'd take in a well functioning non-corrupt market, for example employing the Kelly Criterion, that you would encounter were you to be liable for the risks your trades have. ↩

This post is part 8 of the "Metals" series: